This year I read not one, but two books about or by famous Russian male writers’ wives. If there are more of them, which I am certain there are, I would like to read those, too. The first one was Véra: Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov, and I found it via an interview with the writer, Stacy Schiff, in the Paris Review. She was discussing how difficult it was to write a book about someone who worked so hard to excise herself from a narrative—the narrative of her husband’s career, of his genius—and about the absence at the heart of this book about a woman who did not want to be found. Absence, presence, women—those are the words that set things off in my brain. Right away I ordered the book at my local bookstore, which was also at the time my place of employment, and although I do not usually read biographies I read this one and loved every page of it.

Then some other article somewhere sent me to Nadezdha Mandelstam’s brilliant, chilling, disturbing, insightful memoir, Hope Against Hope, and I wondered if I should devote my life to the study of books by famous Russian writers’ wives, because it was the best thing I’d read in a long long time. Nadezdha Mandelstam was married to Russian Jewish poet Osip Mandelstam, who died, under circumstances that were never revealed to Nadezdha, in a forced labor camp sometime in 1938. The account of life in Soviet Russia alone is devastating. But what struck me most about the book was the way Mandelstam watched and understood the people around her, her deep attention to the things that happen to individuals under totalitarian rule. One friend, she writes, “told me I should not allow anyone into the house unless I had known him all my life, to which I always replied that even such friends might have changed into something different. This is how we lived, and this is why we are not the same as other people.” One question this book begins to answer is: What does fear do, to individuals and to a society?

There are some connections to our own present moment that perhaps I do not need to spell out.

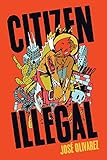

I also read some really good poetry this year: Morgan Parker’s fantastic Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up at Night; Tommy Pico’s ecstatic, hilarous Junk; Danez Smith’s ravenous [insert] boy; Natalie Eilbert’s Indictus, which I’ve been thinking about nonstop ever since (and talking about to just about everyone I know). I bought José Olivarez’s Citizen Illegal at his reading in Madison, Wisconsin, because of my boyfriend; I read Elif Batuman’s The Idiot (not poetry) and was embarrassed by how much I loved and related to it. (One underlined quote, which I then copied out into my notebook like a true adolescent: “I get that you despise convention, but you shouldn’t let it get to the point that you’re incapable of saying, ‘Fine, thanks,’ just because it isn’t an original, brilliant utterance.”)

And I read a pocket-sized selected edition of W.H. Auden all winter and into the spring, for comfort and for elucidation, in times of fear and uncertainty and devastating politics and flights cancelled due to Midwestern March snowstorms. Back in Brooklyn, at a strange moment of in-between-ness, I stumped up and down the perimeter of mostly frozen Prospect Park and recited Auden to myself. These two stanzas about birds and flowers, from “Their Lonely Betters,” particularly got to me:

Not one of them was capable of lying,

There was not one which knew that it was dying

Or could have with a rhythm or a rhyme

Assumed responsibility for time.

Let them leave language to their lonely betters

Who count some days and long for certain letters;

We, too, make noises when we laugh or weep:

Words are for those with promises to keep.

More from A Year in Reading 2018

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The post A Year in Reading: Jacqueline Krass appeared first on The Millions.

from The Millions http://bit.ly/2zWhS7R

No comments:

Post a Comment