Tyrese Coleman’s debut, How to Sit, defies easy categorization. It’s a slim book—about 120 pages—that blends essay and fiction. A finalist for the PEN Open Book Award, How to Sit is an unforgettable meditation on family and home—how our families both damage us and make us who we are; how we form our own families and how we find our place in the world.

Coleman and I recently discussed the book’s unusual blend of fact and fiction, as well as the process of publishing with a very small press.

The Millions: From the beginning, this collection plays with the line between memoir and fiction. Often memoirists will include a caveat that their memories are fallible, but they strive to present events as accurately as possible. In your opening author’s note and throughout the book, you actively embrace and explore the blurry line between what happened, how you remember it, and how you’d prefer to remember it. Why did that structure work so well for telling these stories? Do you think more writers should try playing in that space?

Tyrese Coleman: There was something freeing about being able to lean into the way my memories presented themselves in my head rather than shading them with research or other factual evidence. There is a poetry in memory and emotion that I did not want to lose. So, it would’ve been dishonest for me to make a claim that everything was as accurate as it could be. But I will say that it depends on the piece. Not every piece was drafted with the intent to blur lines; it was more to create a particular voice. So, there are definitely essays in this collection that are factual, yet because they incorporate some memory or emotion, the language is going to be more fluid.

I can’t say what other writers should and should not do, but I do think they should consider eschewing the concept that memoir has to be nonfiction. This is the kind of statement someone could read and say, “That’s bullshit.” But often, when someone makes up a part of their memoir, they’re afraid to admit it’s been fictionalized or to explore why they feel like they need to make shit up. Instead, they should admit that it’s not-quite-fiction or not-quite-nonfiction but that the emotion you feel coming from the page is completely true.

TM: The idea that memoir doesn’t always have to be 100 percent true (to the best of the writer’s ability) and that’s okay—whew! That’s a little hard for me to process. But you’re not saying that we should all be like James Frey. Quite the contrary, you’re careful to label your work at that intersection of truth and fiction, rather than calling it a memoir when it’s not quite a memoir. Would you say it’s all right, even encouraged, to explore that space—but to call it what it is?

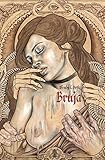

TC: No, I’m saying memoir doesn’t have to be nonfiction and that you can call it whatever you want. I think the best example of this is Wendy Ortiz’s dreamoir Bruja, which is a memoir that includes incantations and dreams interspersed with events and her personal narrative. Is a dream nonfiction? I would say a dream is on par with a memory, in some respects. Does the fact that they both occur in your head, your subconsciousness, mean that they aren’t true? That memory and that dream are true for me and true for Wendy. Does that then mean that we aren’t sharing a part of our life story?

TC: No, I’m saying memoir doesn’t have to be nonfiction and that you can call it whatever you want. I think the best example of this is Wendy Ortiz’s dreamoir Bruja, which is a memoir that includes incantations and dreams interspersed with events and her personal narrative. Is a dream nonfiction? I would say a dream is on par with a memory, in some respects. Does the fact that they both occur in your head, your subconsciousness, mean that they aren’t true? That memory and that dream are true for me and true for Wendy. Does that then mean that we aren’t sharing a part of our life story?

But this isn’t only about memoir. I am currently reading The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo. It is a novel-in-poems. So where do we put this book? On the young adult fiction shelf? On the poetry shelf? What makes it one thing over the other? The fact that her publisher has put the words “a novel” on the book jacket because novels sell more than poetry? All of these labels feel arbitrary to me. The book is amazing, regardless of its genre.

But this isn’t only about memoir. I am currently reading The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo. It is a novel-in-poems. So where do we put this book? On the young adult fiction shelf? On the poetry shelf? What makes it one thing over the other? The fact that her publisher has put the words “a novel” on the book jacket because novels sell more than poetry? All of these labels feel arbitrary to me. The book is amazing, regardless of its genre.

The thing that connects all of these examples, though, is that, from the jump, you know what it’s about. James Frey put forth fiction and lied and said it was 100 percent true. Ultimately, you should let the reader know, “Hey, some of this is true and some of this isn’t, but all of it is based on my life and the way I interpret my memories.” If you want to call it memoir or fiction after that declaration or not, that’s on you.

TM: Did fictionalizing some parts make it easier to write about events that may have been traumatic to recall? Did it help protect some identities?

TC: No. It helped with plot, with creating a better story. Writing about traumatic events or hurtful things from my past is not an issue for me. Those things happened and I cannot avoid them. Identities… well, I didn’t do a whole lot of not revealing identities. In the pieces that are not-quite-nonfiction, it is parts of the plot or aspects of the story that I made up. In some instances, it’s just a short story. In other instances, it’s a small line here and there.

TM: I’d read several of these stories when they were published previously. But all together, they create a powerful narrative—the sum is greater than its parts. How did you choose the stories for this collection? What was the revision process like?

TC: At some point, I realized I was writing the same story, or writing about the same thing but in different (or even not-so-different) ways. I kept returning to aspects of my childhood, even when I was writing about a situation as an adult. So, I put them together and, like you, realized that they were even more powerful when put together. When I revised, I had to find a way to make everything feel more than tangentially linked. That meant changing any made-up names, removing redundancies, and coming up with a structure that demonstrated growth.

from The Millions http://bit.ly/2Jeswx5

No comments:

Post a Comment